A story can be described as the simple representation of a sequence of events, with a beginning, a central part and a conclusion, but the best ones (which arouse strong emotions in the reader) close with a profound message. Whether they are real or fictional stories, with a happy ending or a tragic epilogue, all the most effective stories end by communicating their importance to the reader.

Steps

Part 1 of 4: Deciding the Ending

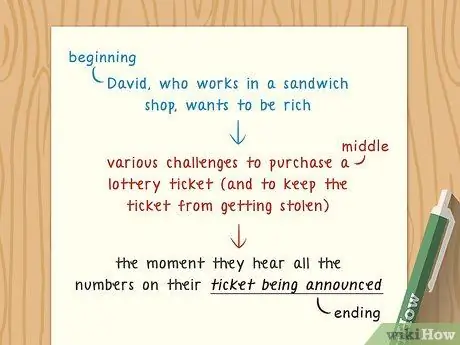

Step 1. Identify the parts of your story

The introduction is the section that precedes all the others, the central part follows the introduction and precedes the conclusion, the ending follows the central part and nothing more happens after it.

- Often the conclusion describes the moments in which the protagonist has achieved his initial goal or has failed.

- For example, your character, who works in a fast food restaurant, wants to get rich and overcomes many challenges to buy a lottery ticket (and prevent it from being stolen). Will be successful? If so, your story may end when the winning numbers are announced.

Step 2. Choose the closing events or actions of the story

This approach is useful if you have the impression that your story contains a lot of exciting episodes full of meaning and that, as a result, it is difficult to find a worthy ending. You have to decide what the climax of your story is, after which no other important events will happen.

The number of actions or events you include in your story matters only in relation to the message you are trying to communicate. Identify which episodes make up the introduction, centerpiece, and conclusion of the story. Once you've chosen an ending, you can shape and refine it

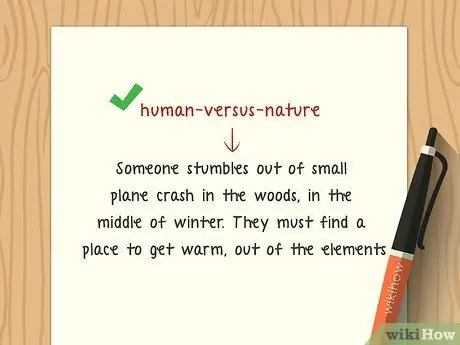

Step 3. Identify the main conflict within the story

Do the characters fight against the forces of nature? Against each other? Against yourself (an internal or emotional confrontation)?

- A figure staggers out of the wreckage of a small airplane, which has crashed in a forest in the dead of winter. He must find a warm refuge, protected from the elements: this is a classic conflict between man and nature. A dancer tries to beat the competition at a talent show: it is a conflict between one person and another. Almost all fights fall into a few general categories, so figure out which one is moving your story.

- Depending on the type of main conflict you are telling, the final events of the story will need to support the development and resolution of that conflict.

Part 2 of 4: Explaining the Journey

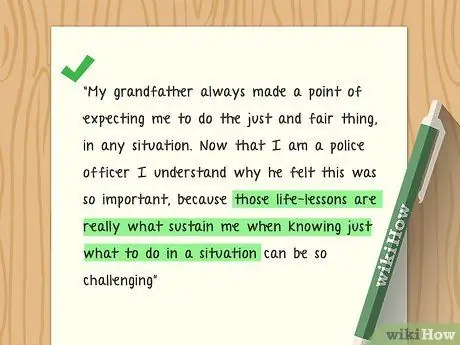

Step 1. Write a reflection on the events of the story

Clarify the meaning of the sequence of episodes you have been thinking about. Let the reader understand why these are important moments.

For example, your story might say: "My grandfather always cared about me doing the right thing in every situation. Now that I am a policeman, I understand why he felt this lesson was so important: his teachings gave me the strength to move forward on occasions when it was really a challenge to understand what was the right thing to do"

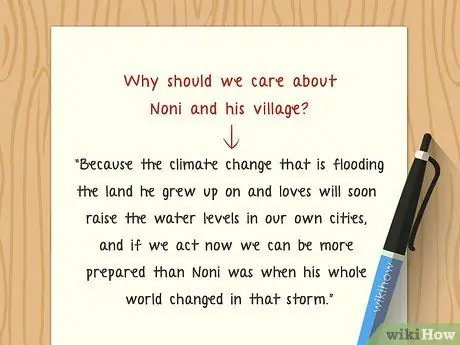

Step 2. Ask yourself how important your story is to the reader

Why should he feel involved in events? If this question has a clear answer for you, reread your work and see if the sequence of actions you have chosen can lead the reader to the same conclusion.

- For example: "Why should we care about Noni and her village?"

- "Because the climate changes that are causing the flooding of the areas where he grew up and that he loves, will lead to sea level rise in our cities within a few years; if we acted from today, we would be better prepared than Noni was. when the storm changed his life."

Step 3. Use a first person narrator to tell the reader the most important elements of your story

You can use your own voice (that of the writer), or that of a character you have created, but you should speak directly to the reader.

For example: "At that moment, I realized that all my hard work and long hours of practice had brought me this far, on that incredible stage, warmed by the dazzling lights of the spotlights, the breath and the voices of all people present inside the stadium"

Step 4. Use a third person narrator to tell the reader the most important elements of your story

You can have another character or the narrator speak for you, and thus convey the meaning of your story.

For example: "Laura carefully folded the letter, kissed it and left it on the coffee table, next to the money. She knew they wanted to ask her many questions, but over time they would learn to find the answers for themselves, just as she did. She nodded, as if she agreed with an imaginary person next to her, left the house and got into an old taxi, which moaned and shivered by the sidewalk, like a faithful but impatient dog."

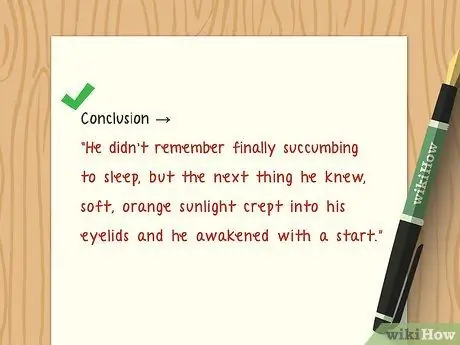

Step 5. Write the "closing part" of your story

The nature of this section depends on the genre of your work. Scientists and academic experts agree that an ending worthy of any written composition should leave the reader with "something to think about". This "something" is the meaning of your story.

- If you are writing a personal or academic essay, your conclusion can take the form of a final paragraph or a series of paragraphs.

- If you are working on a science fiction novel, the epilogue can be a single chapter or the last few chapters of the book.

- You should definitely avoid endings like "I woke up and it was all a dream". The meaning of the story must emerge naturally from the events of the plot, it must not be a label stuck to the text at the last minute.

Step 6. Identify the thread that binds all the events in the story

What does the protagonist's path represent? Thinking of your story as a journey, in which the main character ends in a different place, changed from how it was in the beginning, you will be able to notice the unique structure of your composition and find an ending that suits it.

Part 3 of 4: Using Actions and Images

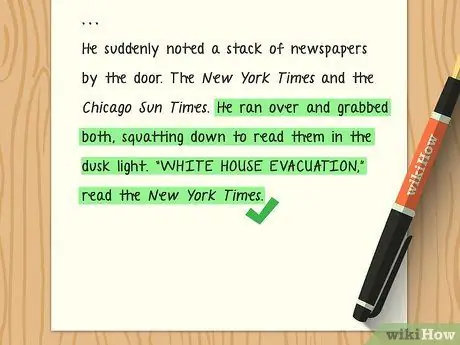

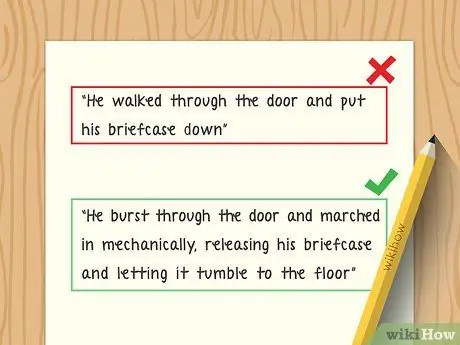

Step 1. Use actions to show what's important (without explicitly saying)

We know that action-packed stories, whether on paper or on film, attract audiences of all ages. Through concrete gestures you can communicate the meaning and importance of your story.

Imagine that you have written a fantasy book, in which a warrior saves a city from a dragon. Everyone is grateful to him, except the local hero who preceded him and who, throughout history, expressed his jealousy for having lost the spotlight. You could end the story with a scene where the old hero hands his sword to the young warrior. Without the characters having to say a word, readers will understand the meaning of that gesture

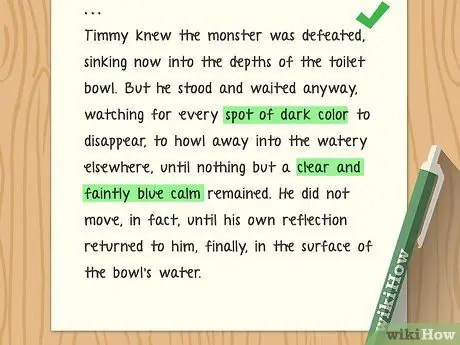

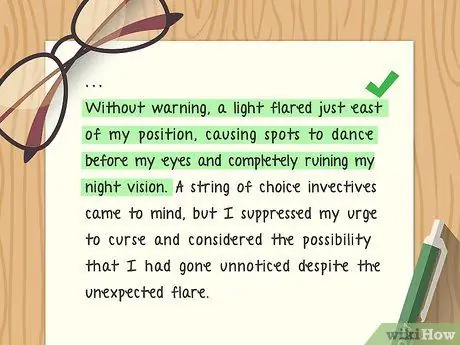

Step 2. Build the ending relying on descriptions and sensory images

Sensory details make us feel emotionally attached to a story, and many great examples of creative writing use these images throughout all stages of the plot. By adopting this technique, and using a language full of references to direct sensations, you will leave the reader with a text full of meaning.

Tommy knew the monster had been defeated and was sinking into the depths of the toilet. He stood there anyway watching, watching every little dark spot disappear and vanish into the aqueous ether, until there was only a hint of blue calm. In fact, there was only a hint of blue calm. he did not move until his reflection on the surface of the water finally returned to return his gaze

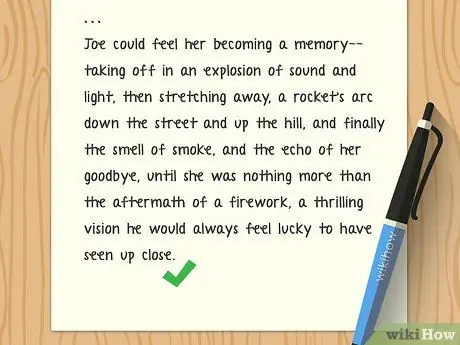

Step 3. Create metaphors for your characters and their goals

Leave clues in your work for the reader to develop their own personal interpretation. Everyone loves stories that stimulate the imagination and leave something to think about. Your storyline shouldn't be confusing to the point of distracting the reader, but you should include rhetorical figures that aren't so easy to understand. This way your work will be much more interesting and meaningful.

For example: "While saying goodbye, Lucia gave gas to the engine of her motorcycle and Giovanni felt that at that moment she had become only a memory: she started with an explosion of sounds and lights, then stretched like a rocket along the road and up the hill, to the point of leaving only the smell of smoke and the echo of his farewell, when it was nothing more than what remains of a firework, an exciting sight, which he had been so lucky to have seen up close"

Step 4. Choose a vivid image

Similar to using sensory actions and descriptions, this approach is particularly useful if you want to tell a story within an essay. Think of a mental image with which you would like to strike the reader, a vision that you believe can capture the essence of the story and use it as a conclusion.

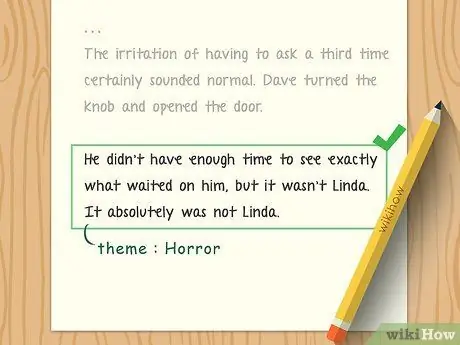

Step 5. Highlight a theme

Especially if you're writing a long story, like an essay or historical novel, you may have introduced multiple themes into it. Focus on a specific theme through images or the actions of the characters, in order to create a unique structure for your work. This approach is particularly useful for stories with an open ending.

Step 6. Recall a moment

Using this strategy (similar to the previous one) you can choose an action, an event or a scene full of emotions that seems particularly significant to you, then "recall" it in some way: repeating it, returning to it with a reflection or expanding what happened and so on.

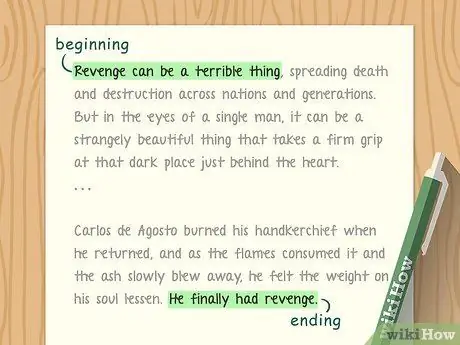

Step 7. Back to the top

This technique, similar to the previous two, suggests ending your story by repeating something you introduced in the introduction and can give a clear shape and meaning to your story.

For example, your story might start with a person looking at a leftover slice of birthday cake, without eating it, and it might end with the same person in front of the same cake. Whether he decides to eat it or not, returning to the beginning will help the reader understand the message you want to convey to him

Part 4 of 4: Follow the Logic

Step 1. Reconsider the plot events to understand how they are related

Remember that not all actions have the same importance and the same consequences. A story describes a sequence of significant moments, but not all episodes in your story lead the reader to the same conclusion. Likewise, not all actions are completed or successful.

For example, in Homer's Odyssey, the main character, Ulysses, unsuccessfully tries to return home many times, encountering monsters and obstacles along his path. Each failure makes the story more exciting, but the most important aspect of the tale is what the hero learns about himself, not which monsters he can defeat

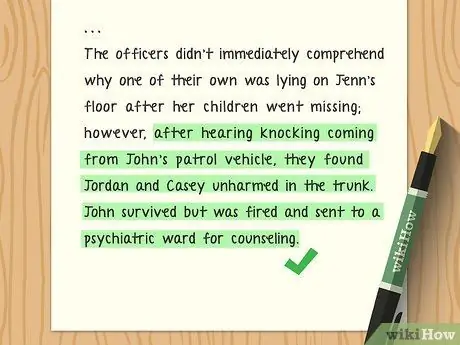

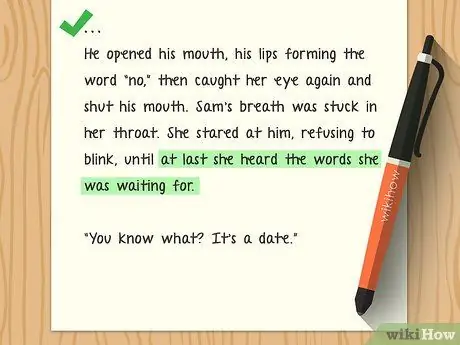

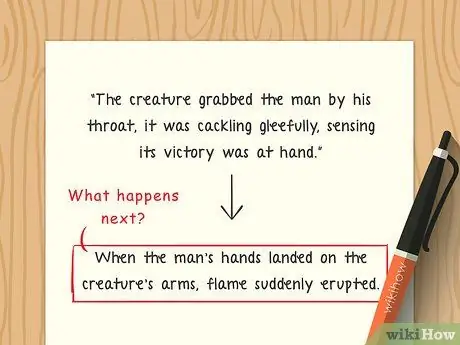

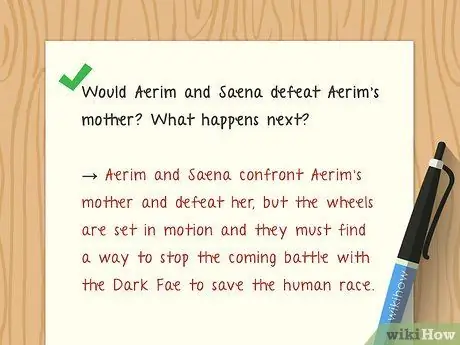

Step 2. Ask yourself, "What happens next?"

In some cases, when we feel too excited (or frustrated) about a story we are writing, we can forget that the events and behaviors of the characters, even in a fantasy world, have a tendency to follow the logic, the physical laws of universe they are in, etc. To find a good ending it is often sufficient to reflect on what would happen in a given situation, according to logic.

Your conclusion should be consistent with what has happened previously

Step 3. Ask yourself, "Why do these events happen in this order?"

Reconsider the sequence of episodes and actions of the story, then identify all those moments when the order of things seems surprising, trying to clarify the logic and the natural flow of the plot.

Imagine your protagonist is looking for their lost dog in the local park when they find a secret door that leads to a fantasy world. Don't abandon the logic you followed at the beginning of the story: describe the main character's incredible adventure, but let him find his dog in the end (or let the dog find him)

Step 4. Imagine variations and twists

Your story shouldn't follow logic to the point of being predictable. Think about what would happen if you changed a certain choice or event slightly and always include surprises. Check all the text to make sure you have inserted enough twists.

If the protagonist wakes up, goes to school, comes home and goes to bed, your story will not touch the chords of many people, because it is a very familiar sequence of events. Introduce elements of surprise: For example, when the character is on the way home, he may discover a strange package addressed to him on the steps of the entrance

Step 5. Ask questions inspired by the natural progression of the story

Reconsider everything you have learned from the events, trials, or details you described. Think, then write down what is missing, what problems or concerns you haven't addressed, and what questions await an answer. Conclusions reflecting on questions may invite the reader to delve deeper into the subject and, following logic, to find more questions than they had at the beginning.

For example, what new conflicts await your heroes now that the monsters have been defeated? How long will peace in the kingdom last?

Step 6. Think like you are a stranger

Whether your story is real or fictional, reread it from the point of view of someone outside the facts and think about what a logical ending might be for a first-time reader. As an author, you may get very excited about one of the events involving the characters, but you should remember that an outside reader may experience different feelings and have a different judgment on which parts of the plot are most important. By distancing yourself from your story, you will be able to observe it with a critical eye.

Advice

- Sketch a track! Before you start writing anything, outline your story line. Think of it as a map that guides you through the story: it reminds you where you have been and what your direction is. It is the only way to always have the whole structure of the story in mind and to understand how to insert the ending.

- Ask another person to read your story and give you some advice. Choose someone you respect whose opinion you trust.

- Pay attention to the genre you are writing. A story included as part of a historical essay has very different characteristics from a horror story. A story for a cabaret night contains different elements from an article for a travel magazine.

- Review your work. When you've decided how to end your story, reread it and look for any script holes and moments that may confuse the reader.